There were a lot of strong board games that came out in 2017, and the limited crossover between the many solid best of lists out there illustrates that. What perhaps stands out the most from looking back over my list of my favourites is how different they all are, and how unique many of them are compared to what we’ve seen in previous years. Every game in this top 10 feels very distinct to me in terms of both theme and mechanics. Here’s a look at the new games I loved most this year from what I’ve played. (As with last year’s list, this uses the Essen to Essen calendar (also used by The Geek All Stars and others) for releases, so I’m considering games released from Oct 13-16, 2016 through the period ahead of Oct. 26-29, 2017.) The information in each bracket is designer(s), publisher(s).

Honourable mention 1: Unfair (Joel Finch, Good Games/CMON): As a huge fan of the Roller Coaster Tycoon video game series, I’ve always been on the lookout for a board game with that sort of amusement park-building feel, and this is the first one I’ve tried that really hits on it. Unfair is very thematic, with all sorts of cool rides, attractions and stands to be built, and there are a lot of interesting game decisions and different strategies here. It’s quite card-comboy, and there are a whole lot of fun combos. This is a game where some of your rides and buildings may be destroyed or closed by other players and the game, so if that bothers you or isn’t a fit for your group, this may not be what you want. But it’s not overwhelming, and there are ways to mitigate it, plus a scenario that takes out negative interactions from other players if that’s more your speed. Overall, it’s a fun game that lives up to its potential.

Honourable mention 2: Lazer Ryderz (Anthony Amato/Nicole Kline, Greater Than Games/Fabled Nexus): Speaking of thematic games based on something in other media, Lazer Ryderz is very much Tron: The Board Game (at least the lightcycle race part) without that license. The game sees everyone laying down X-Wing-style movement templates in turn, capturing prisms by passing through them, and crashing if they don’t make a curve roll or run into others’ laser trails. Something that’s interesting here compared to X-Wing is that it’s not a simultaneous reveal; on your turn, you have the option to increase or decrease speed, then can choose to lay down a straight or curved piece based on the board state in front of you. So while there’s still an element of trying to anticipate your opponent, it’s less intense and easier to adjust on the fly.

You’re also never out of the game even after a crash, and there’s significantly less rules overhead than in something like X-Wing. That’s fitting, considering that this is a light, fun casual game rather than something suited for tournament play. The mild dexterity elements/rules that you can’t pre-measure/die rolls/general zaniness may mean this isn’t a fit for strategy gamers who insist on always being super serious, but it’s an enjoyable filler for those who like Tron, enjoy zooming around the table and are more interested in having fun than destroying their opponents. And the VHS box-style production (complete with gorgeous 80s-inspired art) is perfect.

Honourable mention 3: Ahead in the Clouds (Daniel Newman, Button Shy Games): This is a lovely two-player network-building game that fits well into Button Shy’s collection of minimalist wallet games. It’s simple to explain and plays quickly, but has some interesting decisions in what building to place where when, when to cloudburst and shake up the building connections, and which contracts to target. Recommended as a great two-player filler. It also has a solid solo mode (Stormfront, included in the Kickstarter copies), which is much appreciated, and now it has a sequel titled Feat On The Ground, which I appreciate not just for the pun, but for how it always puts Duran Duran in my head. I’ll have to check that one out.

Honourable mention 4: Sola Fide: The Reformation: (Christian Leonhard/Jason Matthews, Spielworxx/Stronghold Games): Matthews is best known for being half of the team that created head-to-head card-driven historical-themed area-control classic Twilight Struggle, and many of his other games (1989: Dawn of Freedom, 1960: The Making of the President, Campaign Manager 2008) have carried on most of those elements. Leonhard worked with Matthews on 1960, Campaign Manager and Founding Fathers, so there’s a lot of experience going into this one. But Sola Fide stands alone (heh, a bit of a Latin joke there) and succeeds on its own merits.

The head-to-head competition over Imperial Circles does recall Twilight Struggle a bit, but much of the game is quite different, from the pre-game deck construction to the foreign bonus cards. And the way each circle has both a nobles and commoners track is brilliant, making it less appealing to simply cancel what the other player’s doing and more possible to set up big swings. Plus, the game plays in 45 minutes or less. There’s a solid level of historical theme here, especially with the context for each card in the provided booklet, and it’s impressive to see how wide the designers went in their coverage of the Reformation and associated battles, movements and so on, covering people and events from across Europe. It’s a game I highly recommend if you have any interest in the period, and perhaps even if you don’t and just want a quick-playing two-player tug-of-war with some cool deck construction.

Sola Fide is for two players and plays in about 45 minutes. You can read more on it in Sean Johnson’s Too Many Games! review here.

Now, on to the actual list…

10. Spires (T.C. Petty III, Nevermore Games): I love small card games (as we’ll see later on with this list), and Spires is a particularly interesting one. It’s somewhat trick-taking, with interesting decisions for that, from picking which market you compete in to actually competing for cards (especially if you include the Undercutting variant in the rules), but it’s really about making sure you never win more than three cards of any given suit. So, by at least the midpoint, it often turns into more of a trick-avoidance game. But there’s a lot of interesting set collection, too, especially when it comes to majorities in the different symbols (crowns, swords and quills). It’s not like anything else I’ve ever played, which is impressive in the well-trodden trick-taking realm, and it’s a lot of fun. Props here for also including a solid solo variant.

Spires works for 1-4 players and plays in 20-30 minutes. You can read more on it in Eric Buscemi’s Cardboard Hoard review here.

9. The Fox In The Forest (Joshua Buergel, Foxtrot Games/Renegade Game Studios): Speaking of two-player games, that’s a count at which most trick-taking games either don’t work at all or only work with a ton of adjustments. So why not a trick-taking game specifically designed for two? And this one is very well done; the story it’s based on (The Queen’s Butterflies, by Alana Joli Abbott, which you can read on Foxtrot’s site here) is a perfect fit for the central idea of either trying to avoid tricks or trying to win, but not by too much. It’s a head-to-head trick-taking game where each round of 13 tricks sees you shooting for either sweet spot, 0-3 or 7-9 tricks won.

And the story also makes the odd-numbered cards’ special powers make sense; the low-ranking Swan (1) lets you lead the next trick regardless and also can be played against the Monarch (11) instead of the highest-ranking card it would normally draw out, the crafty Fox (3) lets you change the Decree (trump), the Woodcutter (5) lets you draw a card from the deck, then discard a card, the Treasure (7) is worth a point on its own to whoever wins it, and the Queen (9) counts as a trump if it’s the only 9 played that round.

With three suits and 33 cards, plus all the suits having identical cards, this isn’t an overly complicated game to teach, but there’s a lot of strategy here from trying to hit those sweet spots and manipulating those special powers to your advantage, especially when it comes to when you choose to change trump. This is an excellent head-to-head game, especially if you enjoy traditional trick-taking games.

The Fox In The Forest is for two players, and plays in about 30 minutes. You can read more about it in Sean’s Daily Worker Placement review here.

8. The Goonies: Adventure Card Game (Ben Pinchback/Matt Riddle, Albino Dragon): This game is an engaging puzzle of trying to make sure the different locations aren’t overwhelmed by obstacles, managing your hand to do everything from mapping paths to the pirate ship to removing troublesome Fratellis, and dealing with the traps that sometimes show up during your search for treasure. To me, it covers the themes of the movie well, especially when you consider each of the Goonies’ special powers and how they all need to work together to deal with the obstacles that show up. I like this a lot as a solo game, whether working with just one character under the solo rules included or controlling multiple characters. It’s also good with more players, as long as you have a co-op friendly group that isn’t super into alpha gaming.

The Goonies: Adventure Card Game is for 1-4 players, and plays in 30-45 minutes. You can read more on it in Chad Osborn’s The Dice Have It review here.

7. Trick of the Rails (Hisashi Hayashi, Japon Brand/OKAZU Brand/Terra Nova Games): I love trick-taking games and train games, so the description of this as “trick-taking meets 18xx in a 20-minute game” was too good to resist. Plus, I’ve long been a fan of Hayashi, from Trains through Sail To India to one coming later in this list, and Terra Nova Games did a superb job on the packaging of this reprint, from the gorgeous cover art by Ian O’Toole (love the choice of a Hudson locomotive) to the attractive and highly-functional card graphics from Todd Sanders to the excellent scoresheets and even an included pencil (which is a small thing, but is highly useful for taking this to game nights and not having to pause to see if anyone has a writing implement).

And the game itself thoroughly surpassed my expectations; it’s a really clever card game, all about trying to boost one or two railways’ profits while maximizing your stock holdings in those railways, and often doing so by losing tricks instead of winning them. The locomotive selection and allocation concept is particularly interesting, as that can make a railway that looked incredibly valuable worth much less (or vice versa). And the different values of each card (when placed as stations) for each railway are also a good choice, making it that you don’t want to always just play the highest card. This is a game unlike just about anything else, and it may take a couple of plays to get your head around it (many of the groups I’ve taught it to have wanted to play a second one right away now that they get it), but for a 20-minute game, that’s not a bad thing at all. It’s not a full 18xx and it’s not a pure trick-taking game, but it’s a delightful hybrid of those genres.

Trick of the Rails is for 3-5 players and plays in 20 minutes. You can read more on it in reviews from James Nathan of The Opinonated Gamers and Jonathan Schindler of iSlaytheDragon.

6. Nemo’s War (Chris Taylor/Victory Point Games): While there is a cooperative variant included, Nemo’s War is a solo game at heart, and it’s an amazing one. It lets you explore the oceans as Captain Nemo with the Nautilus, battling ships, searching for treasure and natural wonders, striving for scientific discoveries, and fomenting rebellions against colonial overlords. A cool twist is that there are four different possible goals that shift the values of those various options, so what you’re trying to do game to game changes significantly. The encounter deck is also terrific, immersing you in the theme and leaving you with some difficult decisions on how much to risk.

This 2017 second edition comes with gorgeous art from O’Toole, which makes you feel even more like you’re in the world of 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea. Now, Nemo’s War won’t be for everyone; it’s heavily based on die rolls and chit pulls, so there’s a element of luck involved (there are mitigation options, but your rolls will still have a lot to do with your success), it carries a significant amount of setup, it’s much closer to a wargame than a standard Eurogame, and it really does seem best as a solo game. But if that sounds up your alley, this is a voyage worth signing up for.

Nemo’s War is for 1-4 players and plays in 60-120 minutes. You can read more on it in Dan Thurot’s Space-Biff! review.

5. Ladder 29 (Ben Pinchback/Matt Riddle, Green Couch Games): This is a delightful climbing game for those who enjoy them (some examples include Tichu, Big 2, Scum/President/Asshole, Haggis and many more), where play goes around and around, you have to beat whatever’s been previously played (which, in this game, can be singles, pairs, triples, a four of a kind or a run of three or more cards, with four of a kinds also serving as a “flashover” that can beat anything) and be the first to go out. It comes with a deck of four suits ranging from 1-15 (with excellent firefighter art by Andy Jewett), and then five unique cards, the chief (21), lieutenant (18), rookies (0 alone, but the best possible pair together) and dalmatian (0 alone, but wild in a pair).

What makes this one stand out are the hotspots, though. Each round, players draft “hotspot” restrictions that limit what they can play, with the player currently in last getting first choice. Those limits can range from only leading singles to playing or avoiding certain suits in combinations to ending runs with even or odd cards to taking the start player card, which comes with no restrictions at all. But the harder your limit, the more points you get for going out, so there’s a great tension in trying to find something somewhat difficult that still won’t set you back too much. (And hoping someone else doesn’t draft it first.) This one’s been a great success for me both with my regular game group and with more casual gamers, and it’s very customizable; it plays very well from three to five players, works decently with two, and if you want a shorter game, you can just play three rounds rather than to 29 points. Highly recommended if you like traditional card games with a gamer spin.

Ladder 29 is for 2-5 players and plays in 30-45 minutes, or less if you use the included three-round variant. You can read more on it in Dane Trimble’s preview here.

4. Rocky Road à la Mode (Joshua J. Mills/Green Couch Games): What happens if you take the engine-building of Splendor where many cards make it easier for you to buy other cards, the time track of games like Glen More and Patchwork where turn order isn’t fixed, but changes based on how powerful of an action you take, and the cards-as-both-playable-and-payment idea from games like San Juan and Race For The Galaxy? Put it all together, give it an ice cream theme, and throw gorgeous Adam McIver art in as the cherry on top, and you get Rocky Road A La Mode. While the individual mechanisms in this will be familiar to seasoned gamers, the way they interact is quite interesting, from trying to time your time track movement precisely to pick up bonus “rocket pop” tokens to debating about whether to play an individual card as an order to fulfill or as something to fulfill an order. And there are several possible strategies, from starting with no-point, engine-building only cards to going for bigger points right away, and from going all-in on one type of ice cream to try and claim that location to diversifying and getting a less-valuable location, but more flexibility.

However, this is also a quick game that’s easy to sell non-gamers on thanks to the art and the theme, and easy for them to grasp given the limited number of options on each particular turn. And it’s one I keep being able to get to the table, thanks to its versatility as a game-night filler or a game to play with a lighter crowd. I wrote a Kickstarter preview of this back in July 2016, liked it so much I backed for a full copy, got that copy this year and have played it a ton since. And I’m looking to play it much more in 2018.

Rocky Road à la Mode is for 2-4 players and plays in 20-30 minutes. You can read more on it in Stuart Dunn’s review here.

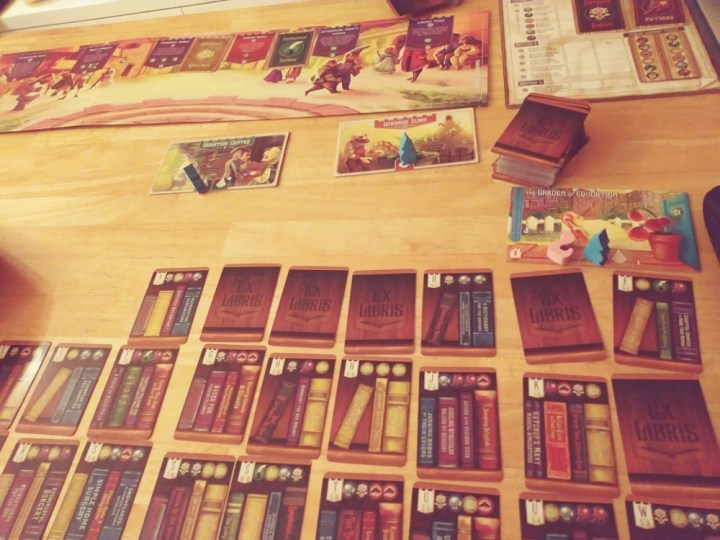

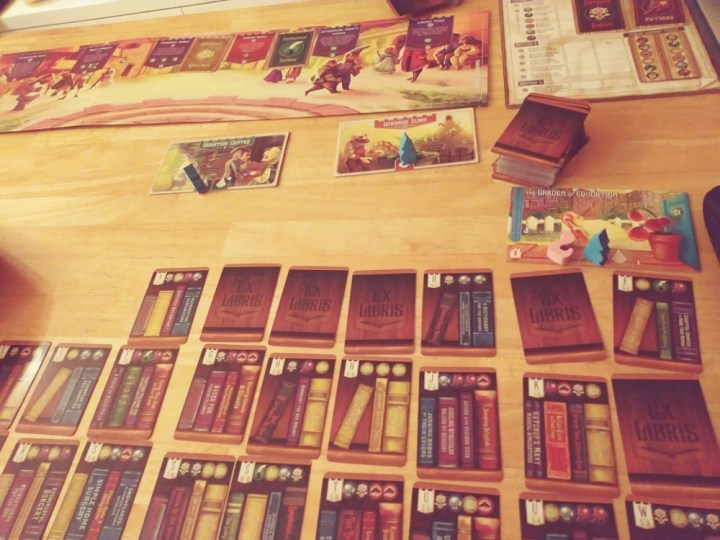

3. Ex Libris (Adam McIver/Renegade Game Studios): A game about building libraries in a fantasy setting sounds amazing in the first place, but it’s the execution of Ex Libris that really takes it to a new level. The worker-placement and set-collection/tableau-building mechanics are familiar and should be easy enough to explain to newer gamers, but there are so many interesting twists here that there’s a lot for gaming veterans to explore. In particular, the idea of having to have your shelved books in alphabetical order is great, especially when many of the locations allow you to shelve books you gain, raising questions of if you do that and risk locking yourself out of books you draw later, or wait to shelve but have to take extra actions to do it.

The constantly-varying locations are another excellent twist, as they feel quite distinct, making it so you’re not just doing the same thing round after round. This also has the advantage of making the spot to take the first player marker more important than it is in many worker-placement games. (And it comes with a draw of cards based on how many assistants you’ve already placed, avoiding the null turn of “I’ll just go first next time” and introducing a bit of pressing your luck and reading your opponents on how long you can afford to waste.) The Tigris and Euphrates-style scoring element of scoring points multiplied by your lowest category is great, making you chase variety, while the individual goals reward you for specialization. And the solo game is awesome as well, a variable-difficulty puzzle with you battling against the discard pile.

And that’s just on the mechanics side. The presentation of Ex Libris is incredible, from the hilarious individual names for every single book to the cleverness of the graphic design from McIver and Anita Osburn (which includes the great decision to put all the symbols you need at the top of a card, allowing you to read the title flavor text or not as you wish and allowing cards on a location to be easily stacked) to the bright and vibrant artwork from Jacqui Davis. The custom meeples for each special assistant, from the gelatinous cube to the sasquatch to the snowman, are a terrific touch, making each player feel different. (And those special assistant abilities are a great way to shake things up a little). Each game plays differently thanks to the mix of special assistants in play and when locations come out. And the decision to provide a dry-erase scoring pad and a marker’s an excellent one; that allows for a much bigger scoring pad than the small standard sheets, and it can double as a reference sheet in play (and the outlines of scoring on the town spaces are also extremely helpful for teaching the game), and be used over and over without worrying about running out of scoresheets. All in all, this is a superb package.

Ex Libris plays 1-4 players in 45 minutes. You can read more on it in Jennifer Derrick’s iSlaytheDragon review here.

2. Yokohama (Hisashi Hayashi, OKAZU Brand/Tasty Minstrel Games): Yokohama first came out in 2016 in Japan, but the 2017 Tasty Minstrel re-release is marvelous, especially the deluxe Kickstarter version. With realistic resource tokens, metal coins, and excellent artwork and graphic design from Ryo Nyamo and Adam McIver, this game looks beautiful on the table. And it plays superbly as well. The central mechanic of spreading your assistants out on the board and moving your president to collect them and take actions, with more powerful actions coming when you have more people and/or buildings in an area, is a lot of fun, but that’s only part of the game. You also need to figure out which technologies and contracts are the most helpful, both from a flag-matching set collection perspective and from what they actually do, plus compete for area majority on the church and customs boards.

There’s a lot of potential for brain-burning here, and a lot of indirect player interaction; you generally can’t take an action where someone else’s president is standing, and you have to pay them if you move through an area with their president, so everyone’s movements on the board matter, as does their selection of the technology cards and contracts you want. But there’s enough flexibility that you can almost always still accomplish something even if it’s not your first choice, and you can plan out enough options in advance that turns usually don’t take too long. And there are lots of different strategies to explore, and the modular setup of the board affects how each game plays out, as do what technologies and contracts come out when.

This is quite different at different player counts, too; I’ve played with three and four players, and the four-player game actually feels more open thanks to the extra locations involved, including two of almost everything. The three-player game can feel tighter with more restrictions based on what your opponents do, and that can be a good or bad thing based on your playing preferences. I haven’t tried it with two players yet, but that setup looks promising as well. This is a game I’m very glad I got this year, and one I look forward to continuing to play and explore for years to come.

Yokohama plays 2-4 players in 90 minutes. You can read more on it in Chris Hecox’s review here.

And, last but not least…

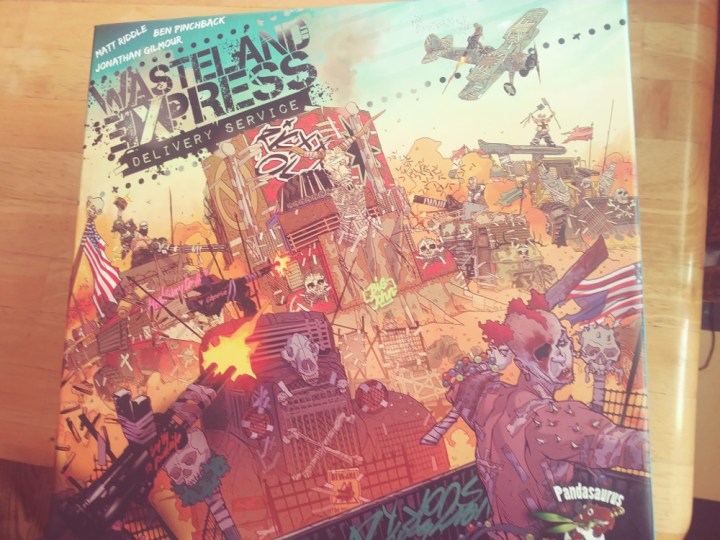

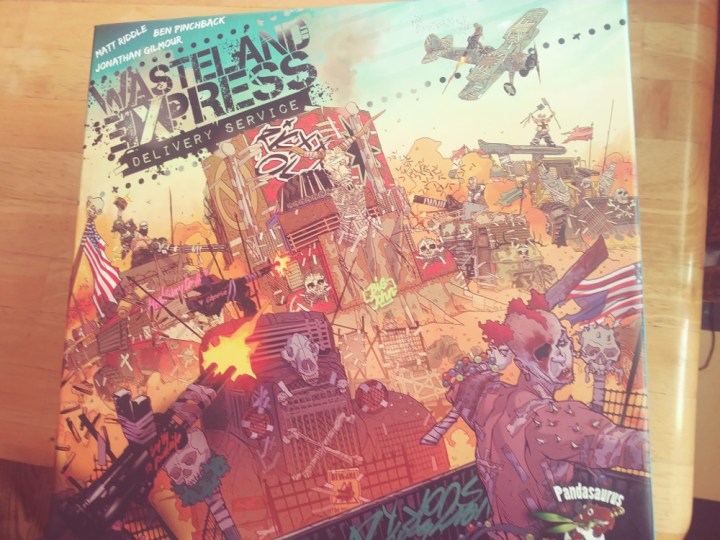

The Board And Game Game Of The Year: Wasteland Express Delivery Service (Jonathan Gilmour/Ben Pinchback/Matt Riddle, Pandasaurus Games): Some of my favourite games involve pick-up and deliver mechanics and fulfilling contracts, including Merchants and Marauders and Shadowstar Corsairs. Wasteland Express has some familiar elements from those, but is very much its own thing, offering a highly-thematic Mad Max-style experience. A lot of thought went into the backstory of the world, the different factions, the special locations and personalities, and the delivery company and its drivers, and the gorgeous terrain art, miniatures and card art really help immerse you in that world. A whole team worked to put this together, from Riccardo Burchielli’s illustrations to the graphic design from Jason D. Kingsley, Scott Hartman and Josh Cappel and the 3D renders from Justin Bintz. And the GameTrayz plastic inserts to hold everything are amazing; it takes time to sort everything into them the first time you open this box, but they make individual game setup, takedown and storage really easy, and dramatically speed up the game.

As for gameplay, this is a sandboxy game with plenty of different strategies and elements to explore, including zipping around the board quickly (the additional momentum from continuous moves without stops is a nice mechanic, as are the limits on which actions you can take each round), spending a lot of time on deliveries to upgrade your truck, focusing on the public contracts or drawing private contracts. The truck upgrades give you lots of different paths to pursue, from extra movement to extra hauling to boosted combat capabilities and more. And each individual action you do resolves relatively quickly, so there’s less sitting around and waiting for your turn than there is in many games like this.

Also unlike, say, Merchants and Marauders, the focus here is more on the deliveries and contract fulfillment and less on the combat;. There’s no actual player-to-player combat unless using a variant, and combat doesn’t have the harsh consequences it does in some other games. But that’s great for the purposes of this one; combat still matters, and can be an important part of completing objectives or gaining resources, but things never get all that disastrous even if you lose, as you only take some damage (and there are ways to repair it, and no way for your truck to be destroyed). And the market is often changing, and quite important, so there’s a bit of an economic side here as well. Overall, this is a more Euro-style take on a thematic pick-up-and-deliver game, and it works quite well. In fact, there are even some elements of train games (a not-so-secret love of mine) in this, particularly the contract-based crayon rails games like Empire Builder. And the mechanics here all fit together well and are fun, as to be expected from Riddle and Pinchback; there’s a reason this is the third game from those guys in this Top 10.

I really appreciate the decision to include an (optional) campaign with eight scenarios to work through in addition to the free play mode. Most of the scenarios don’t change things that much from a strict gameplay perspective, with some only altering the public contracts, but the flavour text for each is awesome, and the continuous story builds the immersion even more. And the ones that do change the rules up more do so in interesting ways. Beyond that, while the game doesn’t have an official solo variant in the box, it’s quite easy to set up and play solo in several different ways, racing against the clock to see how quickly you can fulfill contracts (easily tracked by the event deck, where you flip one card each round), moving raider trucks towards yourself on the roll of a die if you want some more opposition, or even testing out this Grand Lord Emperor Torque’s Revenge variant a BGG user came up with. (I haven’t tried that one yet, but it looks fun.)

Overall, Wasteland Express Delivery Service is an excellent game, one that balances Ameritrash and Euro influences well to bring a ton of theme into a mechanically-solid pick-up and deliver game. It’s beautiful to look at and a whole lot of fun to play. And who doesn’t want to deliver packages in a post-apocalyptic wasteland? That’s why it’s my choice as the 2017 Game of the Year.

Wasteland Express Delivery Service is for 2-5 players in 60-120 minutes. You can read more on it in Alex Bardy’s review here.

Here’s a full look at all the games in this year’s Top 10 and honourable mentions. Thanks for reading!